How Do You Know?

How do you know that? That is one of the most frequent questions I am asking my students in class when they respond to a question. I want to see if they are aware of their answer and how they came to that conclusion. The same goes for claims and posts on the internet today that give us misinformation- we need to know whether or not the post is actually giving us valid and accurate information.

Just like with all the ads and giveaways that appear on our phones, they seem too good to be true. Majority of the times they are feeding us false information that is often believed. For instance, “Day after day, people fall prey to them, hope they are true, and share the misinformation with your friends” (Turner & Hicks, 2017, p.104). This becomes an ongoing cycle, where we see something someone else claims through a post and reinforce it by reposting it for other people to also believe.

Example from Facebook

The Solution

"Simply hitting like on someone else's post is an endorsement, an act of arguing in the real world" (Turner & Hicks, 2017, p. 108). When we repost or like and comment the post, we are essentially agreeing and supporting what the argument is behind the post. What if we taught our students to stop and think if the post is true before they post something or like someone else's content? How can we get students to approach social media differently so they really know what they are arguing?

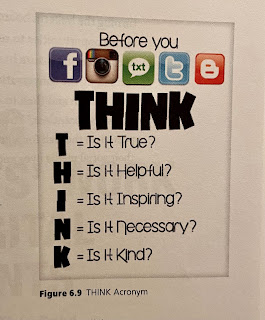

It needs to start with the content of the post and identifying whether or not it is really true. To do this, a process of "vetting" the sources must be done. This can be done before a post is published or after someone else's post is active and you are deciding whether or not it is accurate. The "MINDFUL" acronym for this process stood out to me in the reading of Argument in the Real World, since mindful is exactly how I want my students to be with what they post. By using simple questions that could be modified for younger students, these questions could be the criteria that students have to think through before they post or repost. (see the image below for example questions students could ask themselves)

References:

Turner, K. H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Argument in the Real World: Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts. Heinemann.

Grace,

ReplyDeleteI think this is an incredibly important thing to teach our students: to think before they post, comment, or even hit "like". I like that acronym THINK -it is simpler than MINDFUL, and therefore students, especially younger ones will remember it. Slowing down and not reacting or posting emotionally is a maturity habit that must be learned. As Turner and Hicks (2017) note, "Individuals often respond emotionally to what they read on social networks, posting or reporting without critically analyzing the argument being made" (p.104).

Also - asking them that "How do you know?" question is critical. There was a study done back in 2016 (I am really hoping things have improved since then) that found adolescents and young adults were sorely lacking the skills to assess online information sources (Domonske, 2016). We have a responsibility to help these students be savvy consumers of information on the internet.

References

Domonske, C. (2016). Students have 'dismaying' inability to tell fake news from real, study finds. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/11/23/503129818/study-finds-students-have-dismaying-inability-to-tell-fake-news-from-real

Turner, K.H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts: Argument in a real world. Heinemann

Grace,

ReplyDeleteI wonder, after reading your post, if it is in the best interest of students to utilize social media in instruction, when trying to teach students that much of social media is a place where fact-checking does not have to exist. Your quote “Day after day, people fall prey to them, hope they are true, and share the misinformation with your friends” (Turner & Hicks, 2017, p.104) just leads me to think about the mechanisms of learning that students will engage in. If they hear the same thing 10 times, or the actual true thing once, which will make the larger impact. If a student's experience happens in the saturation of social media, how will they learn the distinctions? While I agree we have to teach them how to spot misinformation, and certainly some social media examples would play that part, should that learning experience take place within the confines of a social media platform? Otherwise, could the lesson not be taught using the framework of traditional argumentative/persuasive writing, where sources must be evaluated, etc. Wikipedia has had editing and is actually fairly well-vetted information, yet it still is not accepted as a reputable source by almost any academic journal or institution. I'm still very torn on the use of social media platforms as a learning venue. Lee's study from Domonske (2016) might make my point even better than I considering the level to which people could not adequately assess online sources for their validity. I'm not sure that immersing students in that environment is the best way for them to learn discernment of it.

References:

Domonske, C. (2016). Students have 'dismaying' inability to tell fake news from real, study finds. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/11/23/503129818/study-finds-students-have-dismaying-inability-to-tell-fake-news-from-real

Turner, K.H., & Hicks, T. (2017). Teaching adolescents to read and write digital texts: Argument in a real world. Heinemann

References: